PDF: BUILDING RECONCILIATION with the Tiny House Warriors Poster Sample

What I’ve been up to lately…

I am now pursing a PhD in Political Science, specializing in Canadian Politics and Indigenous Nationhood, at the University of Victoria in Victoria, B.C.!

I successfully defended my MA thesis, “Armed with an Eagle Feather Against the Parliamentary Mace: A Discussion of Discourse on Indigenous Sovereignty and Spirituality in a Settler Colonial Canada, 1990-2017” in October 2017.

Abstract: Canada 150, or the sesquicentennial anniversary of Confederation, celebrates a nation-state that can be described as “settler colonial” in relation to Indigenous peoples. This thesis brings a Critical Religion and Critical Discourse Analysis methodology into conversation with Settler Colonial and Indigenous Studies to ask: how is Canadian settler colonial sovereignty enacted, and how do Indigenous peoples perform challenges to that sovereignty? The parliamentary mace and the eagle feather are conceptualized as emblematic and condensed metaphors, or metonyms, that assert and represent Canadian and Indigenous sovereignties. As a settler colonial sovereignty, established and naturalized partially through discourses on religion, Canadian sovereignty requires the displacement of Indigenous sovereignty. In events from 1990 to 2017, Indigenous people wielding eagle feathers disrupt Canadian governance and challenge the legitimacy of Canadian sovereignty. Indigenous sovereignty is (re)asserted as identity-based, oppositional, and spiritualized. Discourses on Indigenous sovereignty and spirituality provide categories and concepts through which Indigenous resistance occurs within Canada.

Read it here: https://ruor.uottawa.ca/handle/10393/36887

Where you can find my work or follow me…

Religion Bulletin: http://bulletin.equinoxpub.com/?s=stacie+swain

Academica.edu: https://uvic.academia.edu/StacieSwain

Twitter: https://twitter.com/StacieASwain

Culture on the Edge: https://edge.ua.edu

Check out my contact details to get in touch!

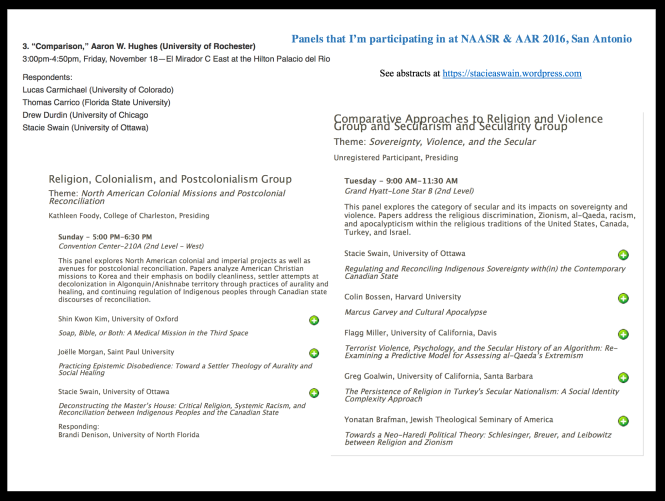

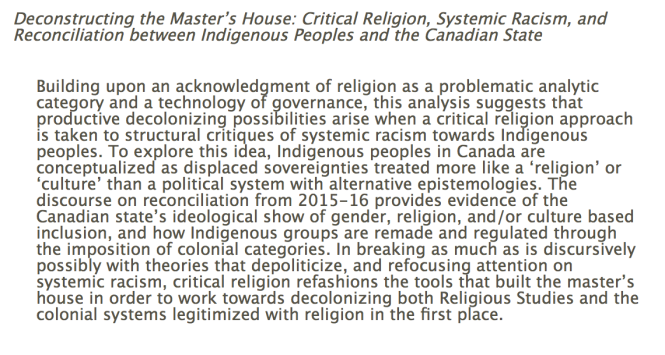

Schedule of sessions that I am a part of at the Annual Meeting of the AAR/SBL and NAASR:

(see my abstracts below!)

For the NAASR session on Friday afternoon, I’ll be responding to Aaron Hughes on “comparison” as a method in the study of religion.

See his paper (and the other 3) here.

And the NAASR program on “Method Today.”

On Sunday evening, I’ll be presenting:

And on Tuesday morning:

Admittedly, it has been MONTHS since I wrote these, but the ideas are there if some of the terminology may have changed. And, excuse the liberal sprinkling of buzzwords.

Hope to see you there and best of luck if you’re presenting. Check out my contact details and shoot me a message if you have any questions, see anything I might be interested in, or want to meet-up!

See Part One

Words matter.[i] When I began to understand deconstruction as a method, I felt like I no longer knew how to speak (I’m still figuring it out). In this sense, I see pedagogy as teaching one not simply how (and not what!) to think but also how to write and speak. I understand critical religion pedagogies as teaching one how to speak and write in ways that are more conscious of the social dimensions (context and implications) of what one reproduces through discursive citation (of concepts and sources). Even then, as my supervisor is fond of saying, “if it’s difficult to step out of the box, it’s even more difficult to keep from falling back into it!”

The discourse on religion coming from a critical theory of religion or a critical religious perspective as offered in the editorials, appears to (or prefers to) remain within the ‘religion’ box without questioning how it came to be or whether it really ‘is.’ The claims made in the CRR pieces under discussion cite and enact ‘religion’ in a performative sense, bringing it into being and reproducing it, manifesting constructions and constructing manifestations. Using the term ‘enacts’ perhaps applies to all scholarship, if to differing degrees: “‘enactment’ can, in general, be understood as a less conscious and willed dimension of reproducing social and political categories.”[ii]

However, as McCutcheon points out in his Theses on Professionalization, “teaching and research are complementary activities, inasmuch as teaching, somewhat like publication, constitutes the dissemination of information gained by means of prior research.” Additionally, “The performative… is always pedagogical, and the pedagogical is always political.”[iii] Scholarship by its very nature performs or enacts a pedagogical performance that doesn’t simply stop at the end of the page.

The CRR editorial asks, “Is it time to find new ways to unmask the processes through which we position our own intellectual tasks?” Absolutely (sort of). For the most part, that’s what scholars who deconstruct and historicize the category and the study of religion aim to do, whether for their own purposes or for the intellectual satisfaction of taking things apart – that would depend on the scholar and the project, and similar scrutiny may certainly be applied to their work. Deconstructing ‘religion’ only to reconstruct it over again but ‘better’ would defeat the purpose of “unmasking” the processes through which ‘religion’ comes to be constituted as an object of study and critique in the first place.

One caveat, ending on the “unmasking” metaphor: I rather doubt that there is something really real, reachable, and readable under the mask, either within scholarship or with respect to that which scholars claim to study – something to be taken prima facie or at face value. The assumption that there are forms of religion, religions, the religious, research, scholarship, and pedagogy that should be taken at face value that can be “unmasked” is perhaps one of the fallacies of constant (re)construction built upon on ambiguous conceptual categories. There will always be cracks in the foundation – unknown, unacknowledged, unrealized, perspectives and interests, waiting in the wings to (re)construct again (and again, and again).

Deconstruction can be used to take ‘religion’ apart not only to rearrange the social features that contribute to the constitution of religion, but also to question how it is that those features came to ‘be’ and to be arranged in the first place. Critical (religion) pedagogies in the study of religion destabilize the ‘givens’ of the field in order to offer new perspectives. Fostering an awareness of the perspectives and aims of a particular approach teaches students not simply to parrot one approach or another, but to evaluate each for the work that it does both on and off the page.

[i] Anecdote: As an early, avid reader who often read words before ever speaking them, words, word usage, and wordplay has always fascinated me. As a young adult, I paid a large chunk of cash to become certified as an ESL instructor. I ended up never using it, at first due to circumstance but afterwards because teaching someone how to communicate seemed like a loaded responsibility. I try to still bring that awareness into my own work and pedagogy.

[ii]Ahmed, “Interview with Judith Butler,” 2.

[iii]Denzin, Lincoln, and Smith, Handbook of Critical and Indigenous Methodologies, xi.

Reposted on the Bulletin for the Study of Religion – April 22, 2016

Recently I wrote a response to an editorial in Critical Research on Religion (CRR).The editorial debates a ‘critical religion’ versus a ‘critical theory of religion’ approach. An earlier piece briefly mentioned in the editorial (and in my post) asks, “Can a religious approach be critical?” and the answer from the CRR editorial board, in short, is “yes.” I’d like to muse on these thoughts a little more by pointing out that we now have three word combinations to consider when we think of what a ‘critical’ approach may entail with respect to ‘religion’:

1) A critical religion approach

2) A critical theory of religion

3) A critical religious approach

What distinguishes the first from the latter two is the contention that, as Willi Braun states, “religion does not exist; all that exists for our study are people who do things that we [or they] classify as “religious.”[i] In contrast, the latter two take for granted that there is something identifiable called ‘religion’ and that one can have the quality of being ‘religious.’ Here we have two claims (similarly named, but rearranged), presuming that #3 above is subsumed within #2. The two claims in question regard:

versus

The pedagogical implications of the two approaches in question can be elucidated by considering not only such wordplay, but also the aims that they claim to work towards and how they do so. The aims of CRR state that, “our goal is not to be pro-religion or anti-religion but to understand religions in both their positive and negative manifestations.”[ii] The authors of the editorial, “suggest a more social scientific construction of the category of religion… It need not have one agreed upon universal definition, since we think such a definition is impossible, but may contain multiple definitions (after all, words have more than one meaning) derived from some common characteristics of the world’s religions.”[iii]

When thinking about teaching this approach, it would entail defining the “category of religion” according to “the world’s religions” (i.e. defining religion by referring to religions).This is, to borrow a nice turn of phrase from Tomoko Masuzawa, “intricately intrareferential.”[iv] If one invokes ‘religion’ enough then it will (seem to) appear, much like the phantasm of ‘Bloody Mary’might as one stares into the bathroom mirror; then, you study what has been invoked as if ‘it’ has always been there, and even though you’re alone in the room, as if you had nothing to do with placing ‘it’ there and naming ‘it.’ From this I gather that a critical theory of religion entails a critical approach to something given to be already and always existing, origins mystified in the processes of construction.

The editorial in question particularly critiques critical religion as having a solely deconstructive approach. To reiterate a quote that appeared in my last post: “scholarship only becomes critical when it uses values to critique sets of social actors and their particular interests… the critique needs to have a goal. It must not only deconstruct but it must construct something better beyond it.”[v]A critical theory of religion then, can perhaps be described as constructive criticism – this approach claims to construct something called religion in a ‘better’ way, using criticism to build upwards upon a foundational concept called ‘religion.’ For if it is a “positive manifestation” then it is to be praised, and if it is a “negative manifestation,” then it is to be improved. This is done according to the “values” quoted above.

The above requires the admission that what has been constructed and classified (or classified and constructed) as ‘religion,’ has been constructed badly in the first place and continues to be. This is where the question of “values” and a progressive narrative comes in – one must have a pre-established notion of ‘good religion’ and ‘bad religion’ if one is to reconstruct it. But good or bad according to whom and in what context? In a pedagogy of a critical theory of religion, does one teach values to students, values beyond those of responsible and rigorous scholarship? Is there a line separating pedagogy from personal and/or institutional ideologies? If not, is there some mechanism in place to ensure full disclosure of that ideology and the potential interests it may serve, or serve to disguise?

In contrast and speaking generally, a critical religion approach is critical of the category of religion and those forms of scholarship that uncritically perpetuate narratives of the good, the bad, and the ugly ‘religion.’[vi]A deconstructive pedagogy might include examining the productive power of these (loaded) narratives in order to draw attention to construction, context, aims, and social implications. In the Twitterverse, it appears that undergraduate students in Alabama are doing just this with respect to ideology and the media. One student concludes a report on the exclusionary politics of news media: “Recognizing how a narrative is being built is an important facet of learning to deconstruct. Through deconstruction, we take nothing on face value, and contemplate why and how things are being represented.”

Thus, what are the implications of the way that CRR represents a critical theory of religion? What are some other representation of a ‘critical’ approach? For example, there’s Matt Sheedy’s recent take over at the Bulletin: “The critical scholar does not merely cast judgments based on an affective and political aversion to the group or practice in question, but attempts to make what seems strange familiar and poses questions rather than providing concrete answers or value judgments.” I would add that the ‘familiar’ be made strange, as well.

[i]This is in “Introducing Religion,” in Introducing Religion: Essays in Honor of Jonathan Z. Smith, unfortunately I only have an electronic copy of the chapter in question at the moment, and don’t know the page number in the book.

[ii]Goldstein, King, and Boyarin, “Critical Theory of Religion vs. Critical Religion,” 4.

[iii]Ibid.

[iv]Speaking of both religion and culture, Masuzawa, “Culture,” 82.

[v]Goldstein, King, and Boyarin, “Critical Theory of Religion vs. Critical Religion,” 6.

[vi] For a more thorough discussion of what ‘critical religion’ is or isn’t according to specific scholars, consult the sources within the editorials discussed.

Earlier today, I read the editorial “Critical theory of religion vs. critical religion” in Critical Research on Religion, 2016, Vol. 4(1) 3–7, by Warren S. Goldstein, Rebekka King, and Jonathan Boyarin.

To give a brief background, from what I gather, since the inception of the journal there has been debate around what exactly ‘critical’ means when it comes to the study of what we’re classifying as ‘religion.’ The triple-authored editorial characterizes three scholars (Russell McCutcheon, Timothy Fitzgerald, and Craig Martin) as representing the “critical religion” approach, then makes an argument for the approach that the three editorial authors represent, that of a “critical theory of religion” (and, why it is different and presumably better than the other).

After reading the editorial, I had some thoughts of my own – perhaps we can continue the rule of three, and have three graduate students weigh in? – and as my thoughts were getting rather lengthy, I decided to post them here as opposed to in a Facebook comment. I would be delighted if anyone has a response, and would like to preface my comments with the admission that they’re shamelessly self-reflexive with respect to my own situatedness and my chosen master’s research project, a working-out-loud of my own positioning and approach. And, I haven’t read the work, except perhaps briefly, of the editorial’s authors, so take my critique with a grain of salt.The particular strand of thought that I want to pull out is:

“As it stands, the approach of critical religion is solely deconstructive and not constructive; it does not build anything… It must not only deconstruct but it must construct something better beyond it. It is only through the use of values and ideals that this can be done.” (Pages 4 and 6)

While now you can see why I used the term “better” above, I’d like to discuss some important points with respect to (re)construction, who gets to do it, and according to whose values and ideals (or interests?). For example, I’m studying the category of religion in reference to Indigenous peoples in Canada, and deconstructing the politics attendant upon its use (by the state). Part of that deconstruction is patently pointing out that it’s not my place to construct a “better” state, but to contribute to making space for more often excluded voices to fill; not refilling that space with my own (privileged) voice, which would reproduce what I critique. As a result, I consciously draw upon Indigenous voices that outline similar interests (and sometimes sources, but I’m not sure about values) and do offer what they see as progressive constructions. I see that as possibly (but not necessarily, because I have critical doubts about my own positive influence), contributing to a discourse on social change – IF anyone wants to use my work for their own purposes, or even if it just makes someone (anyone) think twice about a statement or event.

So, while of course I’m situated/implicated, with the model that I use – that of critical religion, if that isn’t clear yet – I’m also not actively constructing a model to replace what I’ve just attempted to take apart. However, isn’t that still ‘constructive’ in a sense that is precluded by the above quote? Perhaps in a less imperialistic way, at least in this particular context? I find that a critical religion approach allows me to mitigate to some extent the fact that I am non-Indigenous and thus in the context of this literature a settler, and the social implications attendant upon accepting that as an identity claim.

In an academic context, I don’t see it as my place to decide, define, and thus impose and reproduce values and ideals either of or upon those social actors and contexts that I claim to study. This is in part because I am aware that I myself am imbricated in a social and institutional context in which certain values and ideals are often assumed, and privileged. It would therefore undermine my academic interests and yes goals, to presume to construct a new world on top of possible others. The extent to which this strategic attempt at self-effacement might apply (and work) would likely change from person to person, project to project, context to context.

As the editorial states, “[critical religion] is based on a suspicion of universal values and an attempt to socially locate them as interests. Identifying such social loci is essential.” This leads me to venture that the real issue at stake between the two positions that the editorial presents, is “social progress” according to whom, and the assumption of universal values within scholarship as well as outside of it – something “better” or “beyond.” Others prefer to describe and/or acknowledge these presumed values and ideals as another layer of interests, context-specific and socially situated, and equally open to critique.

I quote, but add italics for emphasis: “Yet, scholarship only becomes critical when it uses values to critique sets of social actors and their particular interests. It can only be counter-hegemonic when it reveals particular interests hidden behind proclaimed universal values.”

Indeed, but with the caveat that I am also suspicious of those values claimed in the first sentence.

Before concluding, I’d like to address one final and related point, and bring a third voice into the discourses represented here by the two sets of three. The editorial above can be supplemented by two posts on the Bulletin for the Study of Religion Blog, that recount a social media conversation between several of the scholars above and a few others. You can read part one, and part two. At the end, Craig Martin notes that he finds, “the voices of women in our discussion conspicuous by their absence.” And while Rebekka King is an author of the editorial above and I by no means wish to discount her voice by failing to note that, I am both adding my piece (above) and want to selectively quote another woman from outside of this debate.

While I confess that some of it is beyond me at this point in the semester (at least I can count this editorial towards my literature review, which I should be working on!), I find sections of a post on Sarah Ahmed’s blog relevant, and compelling:

“The promise of the universal is what conceals the very failure of the universal to be universal. …the universal as pure or empty form, as abstraction from something or anything in particular. But remember: abstraction is an activity. To abstract is to drag away. The very effort to drag the universal away from the particular is what makes the promise of the universal a particular promise; a promise that seems empty enough to be filled by anyone is how a promise evokes someone. It is the emptiness of the promise that is the form of the universal; it is how the universal takes form around some bodies that do not have to transform themselves to enter the room kept open by the universal.

And: no matter how convincing feminist and anti-racist critiques of universalism (of how the white man becomes the universal subject) universalism seems to come back up, right up, straight and upright, very quickly. I have also called this mechanism a “spring back mechanism.” An order is quickly e-established because the effort to transform that order becomes too exhausting. Universalism: when you push against it, you become pushy.

Back to the same thing.

Same old, same old.”

And I think that I’ll end on that suggestive note, and add that I am very open to critique and response – I’m a newcomer in the room and I’m not exhausted yet.

photo credit: <a href=”http://www.flickr.com/photos/65609008@N00/138657496″>Sign: Get Social</a> via <a href=”http://photopin.com”>photopin</a> <a href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/”>(license)</a>%5D

The Archbishop of Toronto isn’t allowing Sunday to be a day of rest, but instead is using churches in the city to proselytize the Church’s opinion on euthanasia. According to the media, today Cardinal Thomas Collins’ recorded statement on physician-assisted death is to be shown in approximately 200 churches in the Archdiocese of Toronto, a statement in which he expresses “disturbance” and “shock” at the recommendations made by the parliamentary committee that examined what gets called euthanasia, physician-assisted suicide or death, or the right to die. I have what I think is a healthy skepticism towards the moral evaluations of the Catholic church, particularly when it comes to who gets to decide who lives and who dies.

The two major cases regarding physician-assisted death in Canada are Rodriguez vs. British Columbia (1993) in which the court ruled against physician-assisted suicide, and Carter vs. Canada just last year (2015), in which the court ruled in favour of slowing it. You can read the cases in full here if you feel like delving into it: Rodriguez and Carter.

The language of each case is markedly different, with Rodriguez placing an emphasis on the suicide dimension – according to a simple word look-up, “suicide” appears a whopping 299 times in the Rodriguez transcript, as compared to only 45 times throughout Carter.

While I’m no expert on Catholic doctrines and I’m generalizing, as far as I understand it the Catholic Church considers suicide a sin. As per a post on the Vatican Radio website, “The Catholic Church opposes suicide by appealing to the principle of the sanctity of life and its related principles of the sovereignty of God, human stewardship, and the prohibition against killing.”

The Carter case shifts the focus off of suicide, instead emphasizing the “sanctity of life” – isn’t it interesting that the same exact phrase as the Bishop uses in the statement above, is used by the court throughout both cases – as well as the security and dignity of the patient; instead of focusing on the manner of death for terminally ill patients, the court focuses upon quality of life before death.

This shift in focus does several things:

The culmination of these effects shows a decrease in the Church’s monopoly on death and dying. No wonder this bothers the Archbishop of Toronto – the Catholic Church has long since had a large say in who gets to live and who gets to die, in what happens to bodies and what the Church calls souls. Regardless of recent progressive statements, my skepticism remains regarding the moral views of the Church, and in the use of their doctrines to legitimize domination over others.

The Carter case could be read as the triumph of individual sovereignty over that of the Church, in the sense that the individual’s right to manage their own life and death has been upheld. All the same, I would argue that Carter shows not the simple triumph of freedom but instead increasing bureaucratization and control by the state. Someone, and here it will be the makers of new legislation, then doctors, and then patients, must codify and enact who gets the right to die and who does not.

This alternative reading shows how the issue reveals contestation within and over the ideological apparatuses of the state (according to Althusser, who I’m obsessed with right now), the institutions through which the state reproduces the conditions of production, and thus everyday life. Carter shows a decrease in the power of the Church and reproduction of Catholic ideology, and increasing power accorded to the legal and medical apparatuses through which the values of the current ruling class are reproduced. I’m choosing now not to get into the debate on whether or not this also shows a commercialization of death according to capitalist ideology, but that might be a route worth exploring.

In light of these facts, it may perhaps be more useful to read the statements of the Archbishop of Toronto more in light of power than simple (and unverifiable) concern. The concerns of the interveners in Carter and the only instance in which “freedom of conscience and religion” officially enters into the case align with concerns over power. (As a sidenote, I would argue that the language of the case shows continuity between contemporary issues and Christian influence upon the formation of the state). Para. 130 of Carter states, “The Catholic Civil Rights League, the Faith and Freedom Alliance, the Protection of Conscience Project, and the Catholic Health Alliance of Canada all expressed concern that physicians who object to medical assistance in dying on moral grounds may be obligated, based on a duty to act in their patients’ best interests, to participate in physician-assisted dying. ”

There is an implicit hierarchy created in this statement: at the top, the doctrines of the Church; in the middle, the doctors or nurses who are being asked for permission to obey the Church instead of medical institutions; and at the bottom, the patients, whose own wishes – and best interests, as stated above – in effect become subject to the doctrines of the Church.

To conclude, I’d like to draw out the idea that this issue is not simply one of individual life and liberty, but also one that concerns the formation of subjects, and raises questions around the subjection of individuals to ideologies. The Archbishop of Toronto says elsewhere, “…our society has crossed the boundary into dangerous territory in which people are treated as objects that can be discarded as useless.” I would rebut that this statement actually expresses that the Catholic Church now places people into the category of “objects,” not society at large. Because patients, and physicians willing to uphold the patient’s right to die, are no longer the subjects that the Catholic Church wishes them to be, the Church reclassifies them as objects that are no longer useful to serve the interests of the Catholic Church.

This guy does look concerned, but about what, really?

Source: L’Observatoire Romano/Associated Press

Over the past week or so in Alberta there has been a hubbub about “freedom of the press” in the context of provincial government coverage. When I was tempted to give in to an (ultimately pointless) urge to engage in social media debate, I began to realize that the issue itself brings out some deeper questions around definition, classification, and authority. This analysis aims to elucidate some alternative dimensions of the issue, or at least different ways to think about it. Perhaps then it also serves as evidence for the type of thinking that a humanities degree can involve, with one ceaveat: it ends with more questions than the one it began with.

You can read several accounts of the events in Alberta here and here, but to give a rough sketch:

The Alberta provincial government held several press-only, media-specific conferences, which (at least) two reporters were either not welcome at, or blacklisted from. The two reporters in question both work for Ezra Levant and his right-wing news organization.

Lawyerly letters were exchanged, in which Levant’s lawyer detailed the experiences of the slighted reporters, and the Alberta Justice Department on behalf of Premier Rachel Notley’s government responded, “Our client’s position remains that your client and those who identify as being connected to your client are not journalists and are not entitled to access media lockups or other such events.” (See links provided above.)

Ezra Levant called the Premier a “bully,” began a petition, and began crowdfunding for a lawsuit. (Aside: Can anyone else hear whoops of joy and guns shooting into the air?)

Under the threat of legal action and citing public reaction, the Notley government backed down and reversed their ban, while arranging for a former bureau chief of the Canadian press to review the government’s media policies and offer recommendations.

The article that someone posted on Facebook that I was going to respond to was actually a blog post by a political commentator. This man doesn’t align himself with Levant but it appears that he also wasn’t classified as media or press and was banned from the same events as Levant’s employees. So now we have another piece of evidence – it wasn’t just Levant’s organization that was banned, but presumably this ban applied to others who participate in non-traditional forms of media – those run mostly through websites and blogs, although Levant also appears on TV.

One of the reasons for the ban that was given to a Levant reporter was that she wasn’t an “accredited” journalist. This has sparked a debate around the question, “who gets to decide who the media is?” If there is a general ideal of a “free press,” who defines who is “press”? One article sources the director of a journalism program at a university in Halifax. She says, “The underlying issue, of course, is who gets to decide who’s a journalist… Do you really want government deciding who’s a journalist? I don’t think so. I think that’s a very dangerous path.” This leaves aside the fact that the Sun Media corporation is also knows as an “echo chamber” for the Conservative government (see here and here for examples).

The “who gets to decide who’s a journalist” angle is being thoroughly operationalized in response to fears of a repressive government with a monopoly on defining the press, and therefore the products that they produce – the mediators that produce media through a particular medium. I’d like to consider some alternative dimensions that also relate to the definition of a “journalist,” who gets classified as one, and what authority authorizes this identification.

From this particular situation, we can adduce that there is a category of individuals that become subjectified (made into subjects or a grouping of subjects) as the “media;” this grouping is allowed certain privileges contingent upon that definition, and being classified as such. We might say that the creation and perpetual use of such a category hails, or calls into existence, those who wish to claim the use of the word (and what it signifies) for their own purposes. (Building on Louis Althusser’s work here).

In this particular case, Ezra Levant makes himself and his organization recognizable as such, so that he has access to those privileges. We might compare this the situation in which groups make themselves recognizable as “religions” in order to claim the benefits of such a designation under a “freedom of religion” framework. Elizabeth Shakman Hurd explores such claims in international relations in Beyond Religious Freedom (2015), enumerating evidence for the inconsistent application of the category of religion by law and policy-makers. Maria Birnbaum does something similar throughout her doctoral thesis Becoming Recognizable: Postcolonial Independence and the Reification of Religion (2015), also within the realm of international relations.

However, in order for such a category to be effective, and for rights to be allocated to those who wish to claim them, an agent or institution occupying a position of authority must recognize and affirm such a claim. In an insightful chapter about claims to religious status and authority within the collection Religion as a Category of Sovereignty and Governance, Jeffrey Israel shows how both the original call to existence and the claim of the answering subject or subjects must be met by, “the gaze of publicly ‘authoritative’ recognition” (2015: 217). This point shows how when it comes to defining a category, more is involved than simply self-identification.

In relation to acts of identification, in a different context and to a different authority, Levant chooses not to invoke his identification with the media, despite the fact that it may have worked in his favour. On record in court in 2014 (according to the media), he states to the judge, “I’m a commentator, I’m a pundit… I don’t think in my entire life I’ve ever called myself a reporter.” The author of this particular article (who would presumably be one of Levant’s peers in the context of the Alberta government’s meetings) Christie Blatchford, doesn’t appear to consider Levant a member of the media: the title of the piece reads, “Ezra Levant insists he’s not a ‘reporter.’ On this, everyone agrees.”

Whenever there are rules (policies, law, etc.) about who is and who isn’t x or y, questions of classification enter into the equation and so does the potential for discrimination. In failing to recognize Ezra Levant’s employees and perhaps other bloggers and non-traditional media as “reporters,” “media,” or “press,” the Alberta government classified them as not-those-things, something other. My question in respect to the question of classification in this particular context then, is what does it take to not be classified as a reporter?

The government employee who cited “accredited” shifts the classificatory criterion to the prior recognition of an individual as a subject, in this case as a journalist, but a third-party who is seen as possessing the authority to do so. In a sense, this statement passes the responsibility off to a different institution that presumably has some standard. The president of the press gallery later backpedaled, saying “Journalists are not required to have accreditation from (the legislature) press gallery in order to cover media conferences at the legislature… It has long been the practice that reporters simply present their credentials to security to access news conferences.”

If a year of Latin in my undergrad accomplished anything, it’s that I can state with relative certainty that the terms “accredited” and “credential” both come from credere, which means to believe or trust. Not needing to be accredited implies that no external agent, no-one else, has to approve or place trust in a person as a journalist. If credentials are all that the authority in question requires, no-one needs to actually believe that you’re a journalist – you simply need a piece of paper or plastic that says you are, and perhaps an organization or publication of some sort – this is where the gray area comes in. Some reporters even acknowledge this themselves.

However, due to the fact that in the context of covering the democratically elected government, the recognizing authority is meant to be transparent and accountable to the very people making themselves recognizable. Taking away the rights of some of those people is going to appear repressive no matter what.

In short, with respect to the question: “who gets to decide who’s the media?” The answer is “anyone.” Questions of trust, belief, and sincerity can be left aside upon the production of empirical “proof” that doesn’t actually do anything more than make one recognizable to an authority. How many other contexts might such a framework operate within?

Such a framework leads to the assumption that: Levant produces, therefore he is. Just as a thought experiment, perhaps instead of adducing arguments that are contingent upon subjective states and external appearances (not to mention interpretations), we should be looking at effects in the world. Then we might ask instead: who gets to decide what is media, and is there some standard according to which to evaluate failed media? What are the actual results of recognizing Levant, and his employees as belonging to the same category as those others who produce media?

If so, and that standard is reporting or journaling with the purpose of accurately mediating between an event and a party once removed, then the Levant debate involves doubtful “media” in more ways than one. In fact, Levant has been in court for libel six times that I found in a very basic search, and not once has he won. Levant even has a web domain separate from his media site to solicit support against such accusations – http://www.standwithezra.ca/.

The elephant in the room that I haven’t yet acknowledged in this post is the fact that Levant and Notley have competing ideologies, as Levant’s partisan politics clearly show him at odds with Notley’s agenda as the Premier and leader of Alberta’s New Democratic Party (NDP). I wonder if it’s possible for repression to be viewed in light of prevention – or should the provincial government wait until Levant commits libel (again)? Who pays for that lawsuit, if it’s even a real possibility?

Does shifting the focus to what’s produced instead of the producer shed any additional light upon the issue? Can “freedom of the press” be reconciled with the repressive measures of the state? What happens when a member of the press has a competing, but equally repressive, agenda? Freedom of the press in this context allows for “the media” to serve as an ideological battleground. But can it exist any other way? In other words, is there any such thing as true neutrality?

In the meantime, dear Albertan demos, or people: check your sources’ sources. Wait, am I the media?

I began this post a few months ago, but decided to finish it off now anyways. I think it is still relevant in light of the lead up to the presidential race across the border in the U.S.A., as stereotypically mild-mannered Canadians compare Donald Trump’s bombastic divisive cultural politics to less vociferous ones at home.

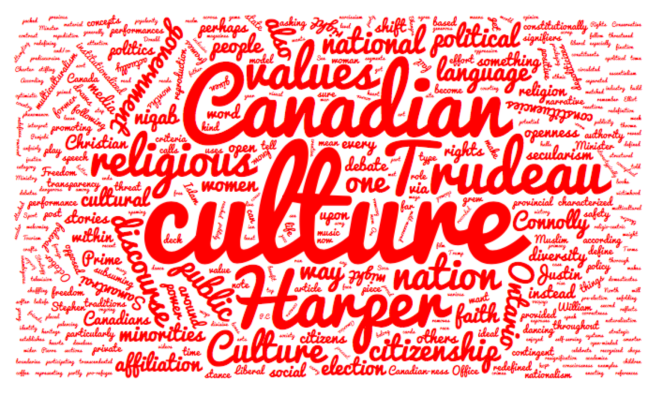

Take a foray into Canadian politics, late 2015… Media portrayals often play a role in reflecting and reproducing hegemony according to the language utilized by state actors. The discourse on culture in Canadian politics, and the shift in that discourse over the time previous to and throughout the federal election in October 2015, is a case in point. Analyzing this shift and the reception of it can reveal the ongoing framing and negotiation of which values are at play in Canadian nationalism and the identification of the ideal “Canadian.” Borrowing from Timothy Fitzgerald, this post illustrates how “language is far from being a game because control of language brings power to the controllers. Politicians [among others] hope to define words in such a way that they confer power and authority” (2000: 88).

Media portrayals often play a role in reflecting and reproducing hegemony according to the language utilized by state actors. The discourse on culture in Canadian politics, and the shift in that discourse over the time previous to and throughout the federal election in October 2015, is a case in point. Analyzing this shift and the reception of it can reveal the ongoing framing and negotiation of which values are at play in Canadian nationalism and the identification of the ideal “Canadian.” Borrowing from Timothy Fitzgerald, this post illustrates how “language is far from being a game because control of language brings power to the controllers. Politicians [among others] hope to define words in such a way that they confer power and authority” (2000: 88).

While Stephen Harper was in power, culture was something that got in the way of such things as citizenship, women’s rights, and public safety. For example, in reference to the well-publicized debate around one woman’s desire to wear the niqab for the public portion of her citizenship ceremony, Harper stated, “We do not allow people to cover their faces during citizenship ceremonies. Why would Canadians, contrary to our own values, embrace a practice at that time that is not transparent, that is not open and frankly is rooted in a culture that is anti-women.”

Several things are interesting in this declaration about culture. The former Prime Minister uses the word “values” – but when religious freedom is a constitutionally protected right (despite the ambiguity in what exactly it protects) and the nation has an official policy of multiculturalism, shouldn’t those concepts characterize Canadian values, as opposed to state-enforced ideas of openness and transparency? Might we read this debate as actually about submission to authority, expectations around conformity, and the limits of diversity? As Ranu Samantrai remarks of frustrated multiculturalism, “the concern is not that Muslims fail to become Christian, but that they fail to follow Christianity’s path to secularism by subsuming their religious affiliation to their national membership” (2008: 331). Harper’s discourse frames this woman’s face-covering as an affront to the nation as a whole. In this situation Muslim women’s bodies, covered or not, become the site on which to contest institutionalized force and the reproduction of ideal citizens.

It’s also important to note that Harper uses the word “culture” and not “religion” or “Islam.” I would venture to say that he espouses a Bernard Lewis/Samuel Huntington-esque approach to culture (one that Samantrai critiques in the article above): that religious affiliation is a (perhaps the) foundational element in determining individual and national “cultural” identities. The religion of the ‘other’ is public, not private; irrational, not enlightened; and cannot be reconciled with a national ethos based upon a model of secularism that supposedly separates from but actually grew out of largely Christian societies and still reproduces Christian-centric bias. William E. Connolly might agree; he calls “secular rationality… hypocritical because it secretly draws cultural sustenance from the “private faith” of constituencies who embody the European traditions from which Christian secularism emerged.” (1999: 91)

Samantrai’s article is valuable for its proposal for the state to eschew religious affiliation as a criterion for citizenship and privilege, which she foresees as beneficial for minorities within minorities (i.e. women within ethnicized constituencies). Her piece, however, begs two questions: can a nation rupture from its own historical contingency in such as way as to align societal norms with constitutionally guaranteed ideals? And, what then holds together the public culture of the nation – or, how might the nation be reconstituted or redefined (if it ought to be)? Connolly’s argument points out that the very idea of a nation, contingent upon vague notions of unity, allegiance, and communication, exists in tension with that of democracy (1999: 90, 87). Connolly suggests that no constituency be given, “the right to occupy the definitive center [or public sphere] of the nation,” which he sees as opening up possibilities for “multiple minorities” to explore multiplicity and intersectionality (1999: 92-3). Instead of subsuming one’s allegiances to that of the nation, his reconfiguration requires people to positively identify with other constituencies based on such categories as gender, language, class, ethnicity, and what may have you. Whether such a desanctified nationalism is possible, I’m not sure.

Returning to Harper, his political decline is also characterized by the proposed “Barbaric Cultural Practices” police hotline. This initiative purported to contribute to public safety when more likely inciting violence against publicly religious persons, particularly given the PM’s obvious opinion of the niqab. As media reports, “The heightened rhetoric over ‘Canadian values’ coincides with a rise in anti-Muslim hate crimes.” Harper in the past year doesn’t sound like the same PM under whom Canada’s Office of Religious Freedom became a thing – although, promoting Western-defined religious freedom abroad perhaps isn’t all that far off from intolerance at home; there is a similar imposition of foreign values in an effort to “civilize” the inappropriately religious subject. (NB: The Liberals might scrap the Office of Religion Freedom.)

Post-October 19th, 2015, and the election of PM Justin Trudeau and the Liberal Party

Shifting for a moment to the provincial level of government instead of the federal, “What does culture mean to you?” That’s what the provincial Government of Ontario was asking via Facebook ads throughout November and December, in the months following the election. The criteria that they provide to define culture is telling of the shift in discourse discussed in this post. Culture is no longer majorly religion nor threat, but is now something that one participates in or shares with others voluntarily. Perhaps a consumer model of culture with the government regulating the market? According to various sections of the Ontario Culture Strategy, run by the Ministry of Tourism, Culture, and Sport:

Culture is all the ways we remember, tell and celebrate our stories, and present and interpret the stories of others.

We tell our stories through:

film and television

recorded music and live performances

books and magazines

visual arts, theatre, dance

crafts

value systems, traditions and beliefs

Not only is culture now redefined as a creative and performance industry, but values are placed within this category. This shuffling of the conceptual deck of cards removes culture from the top of the deck, as this redefinition depoliticizes and domesticates culture as art, performance, material, narrative, and/or heritage. Culture is separated from that dangerous realm characterized by “transcendental narcissism,” as William E. Connolly calls self-serving religio-centric political discourse (8). Culture becomes a positive value, one to be enjoyed, instead of a potential source of threat to one’s way of life.

Justin Trudeau’s popularity grew at least in part through his courting of the segments of Canadian society that benefit the most from the multicultural policy, and those constituents who see themselves as liberal, welcoming, and open (there’s that word again). Trudeau particularly reached out to ethnic minorities. Trudeau is pro-refugee, and opposed Harper’s stance on the niqab. In a pre-election citizenship debate, Trudeau claimed that Harper’s stance “devalues” the citizenship of all Canadians, and that “A Canadian is a Canadian is a Canadian.” The PM also gained publicity and generally positive reactions after videos of him dancing Bhangra to Punjabi music, and “palancing” (dancing) to a Soca song circulated via social media.

Trudeau’s victory speech reads as a repudiation of Harper’s ideological agenda. In an effort to be inclusive he begins: “In coffee shops and in town halls, in church basements and in gurdwaras you gathered. You… told us about the kind of country you want to build and leave to your children.” He redefines Harper’s indeterminate signifiers: “[You want] a PM who understands that openness and transparency means better, smarter decisions.” He references Islam and women’s rights: “Last week, I met a young mom in St. Catharines, Ontario. She practises the Muslim faith and was wearing a hijab… She said she’s voting for us because she wants to make sure that her little girl has the right to make her own choices in life and that our government will protect those rights.” He addresses both religious and cultural diversity: “We know in our bones that Canada was built by people from all corners of the world who worship every faith, who belong to every culture, who speak every language.” And he ends by redefining Canadian values and national culture: “Have faith in your fellow citizens, my friends. They are kind and generous. They are open-minded and optimistic. And they know in their heart of hearts that a Canadian is a Canadian is a Canadian.” (But a Trudeau type of Canadian, not a Harper type).

The second Prime Minister Trudeau depoliticizes culture, partly by participating in performances of culture (as defined by the criteria provided by the government of Ontario), and especially by enfolding “culture” into the national narrative of “Canadian-ness” as something to be proud of instead of threatened by. In a softer way than Harper’s niqab fixation, Trudeau establishes the primacy of national identity over religious affiliation by attempting to open the boundaries of Canadian-ness wider. Trudeau makes openness to cultural diversity cool again – a strategic role for him to step into with his father, former Prime Minster Pierre Elliot Trudeau, recognized for enacting the 1982 Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Ontario government asking, “what does culture mean to you?” via social media in the months following the election reflects the politics of a sort of “people’s culture” that the Liberal party frames Justin Trudeau as representing in contrast to Conservative Stephen Harper’s “war on culture.”

The examples provided above show why, as academics and also as citizens, we should be wary of political essentialism and the naturalization of concepts and signifiers that get thrown around as if they’re prediscursive, unambiguous, and apolitical. Terms such as “culture” carry the weight of the values that get packed into and attached onto them. The concept of culture has the ability to shapeshift according to political aspirations that are contingent upon the promotion and reproduction of such values. Therefore, it’s more important to ask – what does culture mean for you, instead of to you?

*Bibliography in hyperlinks*

The Religion Bulletin, a blog connected to the journal Bulletin for the Study of Religion, was kind enough to publish a piece that I wrote after attending the North American Association for the Study of Religion‘s panels at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion, November 20-24, 2015.

The piece is a reflection on my experience there, on the concept of “Method and Theory” courses, and about the discipline of Religious Studies and my own training within it.

You can find it here: http://bulletin.equinoxpub.com/2015/12/searching-for-method-in-a-sea-of-theory-or-how-i-do-i-even-do-this/.

A big thank you to them for giving me a start in the academic blogging world!